Monthly Archives: November 2010

The Mexican Revolution — 2

The end of hostilities in 1917 led to the single most stable and monolithic systems of government in the 20th century. The triumphant revolutionaries did one thing extremely well: hold on to power. In terms of their social agenda, however, the legacy of Revolution was a mixed bag.

Revolution is tricky to define, more so if applied to any particular conflict. Most definitions go for the idea that a revolution fundamentally reorders power relations within society, a reordering that must benefit those from below, that it must eliminate the ruling elite and establish a new governing class. In terms of Mexico, however, a lot of the scholarship sees the Revolution as incomplete or even non-existent. Sociologist Adolfo Gilly considers it an interrupted revolution, others not even that. For more insight, you could do worse than consider one of British higher education’s hidden treasures; a generation of Mexican historians that are the undisputed world’s best (Alan Knight, Brian Hamnett, Will Fowler, Hugh Thomas).

The failures of the Revolution were many. It did not end the most basic inequalities, poverty remained widespread, land reform (apart from the presidency of Lazaro Cardenas) was piecemeal, insufficient and badly implemented, corruption was never seriously tackled and the state party system was undemocratic. The ruling party (The PRM, which later became the PRI) won every presidential election from 1920 to 2000, held every single governorship until the mid 1980s and would win upwards of 90% of seats in parliament (Mexican vote-rigging techniques are legendary, but it would take too much space to deal with here. A later post, perhaps).

Despite these drawbacks, the Revolution did make a huge difference to many. The end of debt peonage, nationalization of the American oil companies, education, health and public works programmes benefited many. Women were also freer from traditional gender roles. One important area was a new cultural assertiveness that the revolution brought to Mexicans.

This assertive revolutionary culture had both internal and external causes. In the 1920s, the end of WWI saw the end of European dominance in the economic and cultural sphere and the rise of the United States. Outside Europe, WWI was (is) seen as an elitist clash of empires, and this has a negative effect on how Europe is viewed.

Latin America as a whole also undergoes rapid changes including industrialisation and the growth of economic prosperity (especially in Argentina, Uruguay and Chile). This trend leads to a new assertiveness by Latin Americans as they develop their own cultural identity (cinema, radio, music -Carlos Gardel-, poetry -Rubén Darío- ).

Another important international influence was the Russian Revolution and its art and culture. A split began to develop between an old, elitist culture (identified with Western Europe) and popular new forms (US and Latin American).

Mexico led the way in terms of Latin American culture. Influenced by the Revolution, people began to re examine their own roots: What was it to be a Mexican? The government played a leading part in promoting a new culture. Nationalism became a key feature of this promotion. José Vasconcelos, first director of SEP (education ministry) was a central figure in promoting cultural policy. His aims were:

a) To make culture more nationalistic

b) To explore the Indian past and bring it to the mainstream

c) To fight illiteracy (cultural missions and schools crucial in this)

Mexico is now seen as home of the “cosmic race”, indigenous culture promoted as authentic. Revolution glorified as an epic struggle between good an evil. Campaigns against foreign influences (jazz, horchata, women’s flapper fashions), and more importantly against the Catholic Church.

Muralists were one of great cultural forces in revolutionary creative arts: Diego Rivera (married to Frida Kahlo), José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros are the three big names in this artistic movement. Influences on these included Indian techniques and designs and Soviet muralism (art in public spaces, for the people rather than shut away in galleries and collections of the elite and the rich), painted huge buildings; themes too on a heroic scale: Indians, peasants, workers as heroes. Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa are glorified as champions of the poor (even as they were being marginalized politically). In architecture this spirit is mirrored in the new UNAM university campus: buildings are laid out using the pre-Hispanic cities of Monte Albán and Teotihuacán as a blueprint, to create spaces reminiscent of the Aztec past.

By contrast, most novelists are cynical about the Revolution and its outcome (Azuela, Rulfo and later Fuentes). Although most of these writers produced nuanced, intelligent and acute portraits of the conflict, the literate novel-reading elite was always a small minority and unlikely to upset the status quo. In fact the SEP promoted many of these critical novels, showing an openness to criticism and dissent in literary salons that was not tolerated in the mass media. Eventually, however, the dam was going to break.

It all happened in the 1940s, a golden age of Mexican Popular culture: cinema genres (musicals, charro westerns, Luis Buñuel) also championed the music of José Alfredo Jimenez, Pedro Infante and Jorge Negrete: Mariachi music is born. The development of press magazines and the comic book industry saw the country become increasingly literate and westernized. Radio serials (romantic tales, forerunners of telenovelas) grew alongside the music-hall comedians who made the transition to the wireless medium (Cantinflas is perhaps the best known of these). SEP begins to publish and promote the work of Mexican writers such as Mariano Azuela’s novel Los de Abajo (The Underdogs). Culture became increasingly independent of government; irreverent, questioning and sometimes critical, it reflected the Revolution (and Mexico itself) as a multi-layered and contradictory place.

The Mexican Revolution — 1

November 2010 sees the 100th anniversary of the Mexican Revolution: The first major social re-ordering of the 20th century. Its impact abroad was huge, causing panic among elites and putting a glint in the eye of the workers of the world. Mexico predated the Russian Revolution by 7 years and its successes and failures were pored over by Lenin, Trotsky and others.

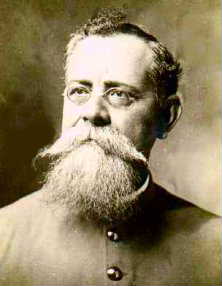

The conflict itself can be (very simplistically) divided into three main stages. The first was the overthrow of the long-standing dictator Porfirio Díaz. Díaz, in power since 1876, was a poster-boy for 19th century Liberalism. He opened up the country to foreign investment, cleared Indians from their land, allowed a wealthy elite to dominate (over 80% of Mexico’s farmland was owned by a mere 840 families). When in the run-up to the 1910 elections Díaz said he would welcome opposition, a lawyer named Francisco Madero took him at his word, standing against him on a popular platform. The dictator promptly had him arrested.

Escaping to exile, Madero called for an overthrow of the regime. Emiliano Zapata, a southern peasant leader, answered his call as did the northern bandit, Pancho Villa. Together, they overthrew Díaz the next year. The old dictator went off to Paris and exile. What Mexico did next was tear itself apart.

Madero was too cautious to satisfy his supporters, too radical for his opponents. At heart, Madero was a liberal too, believing that merely through just laws a more equal society could be made. He freed the press, which was controlled by his opponents, and they began to lambast him. Zapata and Villa wanted radical change and land reform. They did not get it. Soon they retreated to their heartlands to defend their gains. Both refused to disarm and submit to the new order.

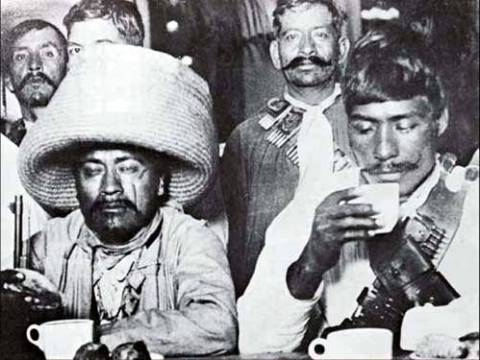

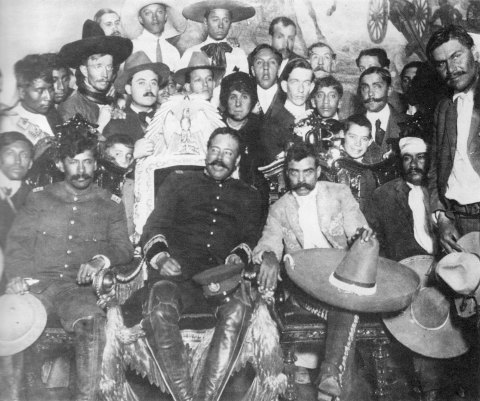

The second part of the Revolution now begins. In 1913, Madero was overthrown by general Victoriano Huerta, who promised to restore the values of Porfirio Diaz (though not Porfirio himself). Madero was deposed, arrested and murdered in mysterious circumstances. Villa, Zapata and the northern governors Alvaro Obregón and Venustiano Carranza rise up against the usurper. Huerta is defeated the next year and goes into exile. Villa and Zapata ride into Mexico City at the head of their armies.

The triumphant revolutionaries were split into two groups. The more radical, Villa and Zapata, wanted land reform and social justice. Carranza and Obregón were more conservative, in the Madero tradition. The third stage of the Revolution involves the power struggle between these groups.

To begin with, Villa and Zapata are left in charge. Carranza takes his troops and retreats to the port of Veracruz (which controls most of the income from foreign trade), Obregón cuts a deal with the CROM anarchist trade union central. Slowly Carranza and Obregón begin to win ground eventually defeating the forces of Villa and Zapata, which again retreat to their rural strongholds.

The 1917 constitution marks a formal end to the fighting. The constitutional convention of 1916 again saw a split between radicals and moderates. The radicals won most of the key battles: an eight hour working day, minimum wage, the right to be paid in cash rather than tokens or company store vouchers were all gains enshrined in the constitution as were land reform, secular education and the control by the state of all sub-soil deposits (which led to the nationalization of foreign oil companies in 1938) and no re-election. The governments in power were, however, moderate in character. Both Carranza and Obregón served terms as president. Villa and Zapata were both murdered by government forces. Obregón himself was assassinated as he campaigned for a second term in office, something specifically forbidden by the constitution.

Most Mexicans look back on this period with mixed feelings. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that the Revolution was betrayed, that all the violence (approximately 1 million people died in the conflict) achieved so very little. All the idealists in this story (Madero, Villa, Zapata, Obregón) died violent deaths well before their time. Only the scumbag dictators, Huerta and Díaz, lived full lives into their dotage. If nothing else, the study of Mexican history teaches you one important lesson: life ain’t fair.

It should also teach you something else; that Zapata lives, that his cry of ‘Land and Freedom’ is still relevant today. That politics is a struggle where you never truly win or lose. There is always a new generation on both sides ready to fight every battle.

So, Feliz aniversario, amigos Mexicanos.

¡Viva México!

¡Viva Zapata!

¡Sufragio Efectivo, No Reelección!

FBS Festive Fifty

Greetings, and festive ones at that. Now, I was going to do you a little selection of Xmas songs. Turns out I didn’t know that many, so I’ve listed the few I actually like and expanded it to cover seven decades of foot-tapping fun. I called it the ‘FloopyBootStomp Festive Fifty’ in a tribute to the late John Peel. Have a cool yule, hepcats.

Festive Five

The FBS festive tracks, brought to you just after bonfire night, because Christmas comes earlier every year (OK, so Jethro Tull’s is about the solstice, which is near enough).

The Trashmen – Dancin’ With Santa

Mercilessly ripped off by the ‘I saw mommy kissing Santa Claus’ thing. No evidence for this rip off, just a hunch that’s all…

Seven maids dance in seven time. Seven druids waiting in a line. Happened to me in Tescos once.

Makes me happy, cheesy old tune that it is. This video is from 1983 (song’s 10th anniversary) and features John Peel himself.

AC/DC – Mistress For Christmas ***

Has an *** which means the track also features on another of my posts (in this case best of the 80s, click on the *** to link)

From the wonderful rock opera/film, Tommy (See the young Ian Hislop in his first ever screen appearance).

50s

Lonnie Donegan – Have A Drink On Me

Muddy Waters – Champagne & Reefers

60s

Bunker Hill – The Girl Can’t Dance

The Kinks – I’ve Got That Feeling

The Trolls – Every Day And Every Night

70s

Gil Scott Heron – The Revolution Will Not Be Televised

Kirsty McColl – They Don’t Know ***

The Stranglers – Daghenam Dave

80s

Crass – Do They Owe Us A Living?

The Leather Nun – Gimme, Gimme, Gimme (A Man After Midnight)

The Playn Jayn – Dig My Own Grave

The Ramones – The KKK Took My Baby Away

90s

Disclaimer: I know nothing about this period of musical history (less than the earlier stuff anyway). Just thought I’d get the apology out of the way.

Juan Luis Guerra – El Costo De La Vida

Half Man Half Biscuit – Joy Division Oven Gloves

21st Century

Again, know nothing at all about current musical trends (Arctic who?). It is why most of the modern stuff I listen to is 60s revivalists/copyists or Spanish novelty records. Enjoy them with milk or on their own as part of a calorie controlled diet.

The White Stripes – Seven Nation Army

Ojos De Brujo – Tiempo de Soleá

The Urges – You Don’t Look So Good

The She-Creatures – Sexy Robot

Circulus – My Body is Made of Sunlight

Grupo Chucumite – El Jarabe Loco

Ixo Rai & Jose Antonio Labordeta – Un Pais

Comic Book Classics — 12

It is uncommon to treat the comic book as an object of transcendence. While many people enjoy comics and champion the form, to support comics in too loud a voice is seen as the preserve of the worst kinds of fandom. Comics do not get their fair share of reverence in the world. The recently broadcast series on BBC radio, The History of the World in 100 Objects showed this same attitude to teapots, coins and stone axes usually reserved for works of high art. It would be a rare individual who would give the comic equal value to such objects. Dylan Horrocks does. He is perhaps the modern comic book’s most articulate champion. In his graphic novel, Hicksville, he goes so far as to give them a totemic moral and spiritual value.

Dylan Horrocks was born in New Zealand in 1966 and seems to have been blessed with an affinity for comics. He claims that his first words were ‘Donald Duck’ and soon began to work as a cartoonist. A spell in the UK saw his work develop further until his return to New Zealand in the mid 1990s. It is in 1998 that Hicksville first appeared, published by the seminal Canadian publisher, Black Eye Comics. It has since been translated into French and Italian and awarded the World Comics Journal’s ‘Book of the Year’. It was immediately recognized as a masterpiece, and here’s why:

Hicksville is the story of a writer, Leonard Batts. Leonard Batts is a partly autobiographical character (A writer and comic book fan, living in London. Although Leonard is a Canadian rather than a Kiwi). His life appears humdrum and pointless in London so, when he gets a commission to write the biography of the most famous comic book artist in the world (a man with the name of Dick Burger), he jumps at the chance. He travels to LA and gets to see Burger up close. He soon realizes that the world of the celebrity has taken Burger over. He is little more than a hack, prodding his staff of artists and writers to churn out endless product with no merit or value. Apart from the fact it sells.

Leonard soon begins question Burger’s motives and actions. He interviews him for the book and talks to some of his staff and fans. After all, he had good ideas once. All his inquiries lead him in one direction: The obscure New Zealand town of Hicksville.

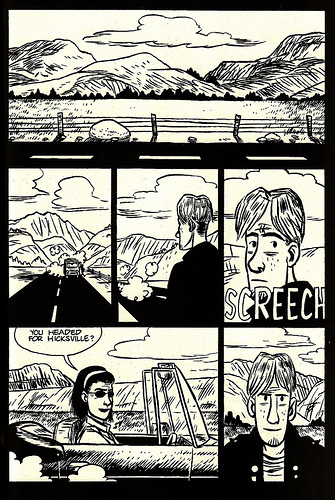

Arrival in Hicksville is not made easier by its remoteness. Leonard gets a lift from a young woman who becomes instantly suspicious when Dick Burger’s name is mentioned. The town, when he arrives is equally reticent. The really strange thing about Hicksville, however, is that everybody there is an expert on comics. Leonard’s landlady, for instance, has Mongolian comics delivered by post and copies of the first issue of Action Comics (famously where Superman first appeared) are just strewn carelessly about. Hicksville is a weird place, one where comics are always present.

The story takes its time and twists to get where it is going. I don’t plan to reveal too much more of the actual plot, but Leonard eventually finds himself in Kupe’s lighthouse; a place guarded by Maori spirits. Inside is a museum full of comics that should have been written; masterpieces by comic book artists that never saw the light of day because the artists never wrote them (a library of comic book Platonic forms?). The artists never wrote them because they were either working full-time for commercial publishers or because they thought they would be no market for their best work.

The lighthouse is the centre of Hicksville, the spiritual home of comics. It is here where the form transcends. Dylan Horrocks makes the link between Maori spirit and comic book art. He makes the dichotomy faced by all comic-book artists clear: do you follow the Dick Burger path, to fame, money, compromise and the extruded superhero product constantly rehashed by Marvel and DC? Or do you take the other road; harder, steeper less financially rewarded but where you create your own vision, make your art as good as it can be? An amazing and thought-provoking graphic novel about what comics are and what they could be. Total genius.